Google Dictionary

mindfulness

/ˈmʌɪn(d)f(ʊ)lnəs/

noun

1.

the quality or state of being conscious or aware of something.

“their mindfulness of the wider cinematic tradition”

2.

a mental state achieved by focusing one’s awareness on the present moment, while calmly acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations, used as a therapeutic technique.

It comes regularly as a suprise to people I coach when I ask them what they thought of a set. People seem to be of the opinion that they are coming to a training session to be dicated at the correct answers.

You might go as far as to say it’s the fault of our overly top down schooling system sapping all the independence and free thinking from our poor defenseless kids. For a lot of people who are willing to part with some money to get help overcoming a problem or a new skill they come with a mindset where they are a blank slate and ready to learn.

Whilst it is better to come ready to learn and not to come with preconceived notions of what you should be learning and how it should be done. It is also useful to keep your critical faculties intact as it will help not only you but also your coach to get you to the correct answers faster. Assuming your coach isn’t some egotistical maniac or a complete narcissistic wanker they want you to get to the correct answers as fast as possible.

Skill learning the basics.

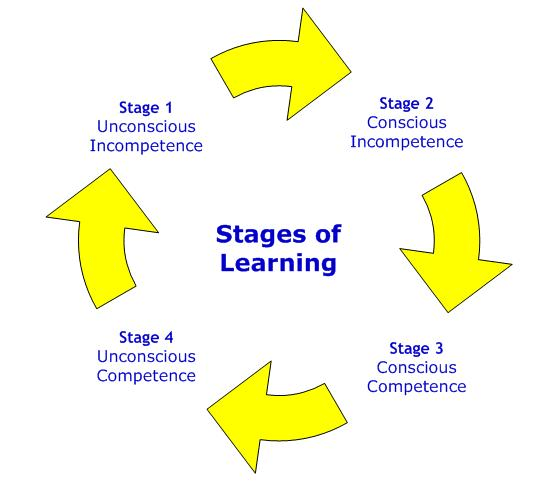

Before we can have a more meaningful discussion on why it is important to be self critical and mindful during training we need to speak a common language. We can break the process of motor learning (or learning in general for that matter) into 4 distinct stages.

- Unconcious Incompetence – you suck and you don’t know why you suck

- Conscious Incompetence – you suck and you can point out why you suck.

- Conscious Competence – You don’t suck any more but you have to really try not to suck.

- Unconscious Competence – you don’t suck anymore and you can’t remember what it was like to suck.

At the very start of learning new skills cues and instructions mean literally fuck all to you until they are put into a context. Watching video of yourself performing the task, of people who are good performing the task and of other beginners is hugely beneficial at this stage.

Being given a lot of different kinds of input as well as a beginner is really useful – tactile, auditory, visual and different cues can all be used to try and find something that makes sense at this stage.

During this stage, if you are encouraged to think for yourself or are encouraged to not just go through the motions you will open yourself up to internal feedback as well as external feedback. As you are performing a movement you are getting sight, sound, visual and proprioceptive (feeling and balance) the entire time throughout every set. Most novices or beginners are trying to be mindful of what they are doing as they are trying to grasp the movement they are doing and trying to understand it.

After a while when you move through the various stages of skill development you will become more confident in what you are doing and eventually, you will slide into unconscious competence. However, this doesn’t mean you know what you are doing.

Unconscious Incompetence as an Intermediate or Advanced lifter

Even if you have had the good fortune to either hire a competent trainer or to have found a good youtube or website with good information on technique and how to develop it. You will slide into a comfort zone with performing the movements. It is important to develop a stable execution of the movement as this is how you are going to develop your strength, training with overloaded volume or intensity with the exercises you want to get better at.

When you slide into this comfort zone it doesn’t mean your form is correct or optimal what it means is that your form is stable and you can do the same movement over and over again and use it to allow an overload stimulus and to get stronger when using it. It is important to always be self critical when warming up or during lighter sessions as it will help you to keep optimising what you are doing and to squash bad habits before they occur.

For lifters who don’t have a coach to keep an eye on them and to keep them tracking in the correct direction they can slide into not worrying about how the reps are performed and to get stuck in a more is more mind-set. The goal of strength training is to get stronger we can all get on board with that statement.

However when you get into training space where you are using either inefficient or more injurious technique and you are not practicing or trying to refine what you are doing while pushing yourself session to session you are both hampering your strength gain and putting yourself in harms way.

How can I be more mindful as a lifter and stop myself getting into common pitfalls of intermediate or more advanced lifters

- Treat the movements like you would any other sport. People seem to think because they are doing these exercises in a gym in their own time it means they don’t have to take it seriously. Think of training as practice you should be trying to evaluate and improve what you are doing every rep and every set where you don’t have to just concentrate on lifting it. When lower intensity and lower fatigue levels allow you should be focusing on your execution and trying to improve upon what you are doing.

- Get someone else’s opinion on it. Ideally, you should have a coach but this isn’t within everyone’s goal set or means. But at the very least you can do is to ask a member of the gym staff, a training partner or just another person in the weight room who is a bit more experienced than you. Getting in other peoples feedback can save you literally years of doing dumb shit during your lifts that are costing you kilos.

- Use objective feedback tools. Pretty much everyone has access to a smartphone so at the very least you should be videoing and watching back working sets to see what your technique looks like. You can also use the smartphone to perform basic video analysis such as bar path tracking there are a number of apps on both Android and IOS platforms. You can also look at other feedback tools such as velocity using something like the Push band to get some other metrics you can use to objectively analyze your performance.

- Use self-reflection between reps and sets – simply asking yourself how did that set go? What did I do well and what could I do better between every rep and set can lead you quickly to things you can try to improve upon and help you to constantly improve on your execution.

- Watch lots of top performers – use Instagram and youtube to watch as much footage of the best people in your sport performing the lifts you want to get better at. When you watch 10,000s of lifts you start to pick up common trends that expert performers all have in common and you start to develop a better understanding of what it is ideally you should be trying to achieve during your reps and sets.

- Keep a journal and write subjective notes – keeping a journal of what you have lifted is great but keeping a journal of how it felt and what you feel you need to work on is even better. Even if you never actually look over it again the simple act of having to be self-reflective over your performance and physically writing it down will aid greatly in your understanding and development.

- Practice mental imagery/rehearsal – taking time either during the day or during rest periods to think through every set of the lift – how does it feel on your back, how does it feel walking out, etc. Going into detail in your head and painting a picture of what it looks, smells and feels like to execute not only good sets but bad sets can really help you to develop your skill set. Mental rehearsal has been shown to have a measurable performance benefit and the best bit about it is that it costs you literally nothing in terms of recovery.

Getting the challenge right

To allow for the best practice you need to stay out of your comfort zone on a regular basis in training but not push so far away that the challenge is to much for you to handle. In his fantastic book peak Anders Ericsson talks about deliberate practice and why it is central to skill learning a lot of the ideas in this article are taken from that book. He talks alot about making practice challenging as it’s only when practice is challenging that you actually develop your skill.

Mindless drilling of a movement with no feedback or increase in difficulty does not lead to improvement it leads to boredom and stagnation.

When the challenge is stretching your skill level then you areach what is known as a flow state, also referred to as being in the zone. When the challenge outstrips your skill you become anxious. When you are under challenged then you become bored and your effort and enthusiasm will drop.

The goal of the program should be to present the correct level of challenge at the correct time.

Making training challenging

- Get the intensity and volume correct. When you are being challenged through both fatigue of volume and seeing your weights go up then there are few times in training when it is more fun or engaging. When the weights are too light, or volume too low training can feel like a waste of time or if the weight is too heavy and volume too high you can feel underprepared and like an injury waiting to happen.

- Use tempo and pause variations to challenge the skill aspect. You can take a light session and make it challenging in a different way by using tempo or pause variations to help to work on weak points in your execution or to give you time to work out the ideal position during different phases of the lift.

- Get the frequency of training right – more sessions means more chances to practice, doing a hard session when under recovered can lead to shitty practice and increase your chance of injury. You need to experiment to see what helps to develop the best.

- Use variation to change the challenge and to stop stagnation. You can use variations such as banded squats to give external feedback that makes the lifter acutely aware of their balance and to force them to brace their upper back better. Other variations can change the balance of a lift or bias towards one joint more than another (i.e. close grip v wide grip bench) which can help to work on weakness and to help a lifter overcome a skill blockage. Another great use of variation is to change the focus of training almost completely or to stop a lifter stagnating their practice. Keeping the training too monotonous can cause burn out and eventually doing the same practice routine over and over again can actually become deleterious to your skill development.

Hopefully this article has given you some things to take away and put into your training straight away and also some ideas you can use in the programing or development of yourself or your athletes you can experiment with going forward.

Marc