As strength and conditioning coaches and especially as strength coaches pretending to be strength and conditioning coaches I feel it is easy to get trapped in the process of worrying too much about how much weight a player is shifting. I think a lot of intelligent people or good strength coaches can end up trying to smash a square peg into a round hole by applying standards or techniques that are fantastic in the world of weightlifting, powerlifting or strongman but make as much difference as throwing a deck chair off the titanic when it comes to preparing an athlete for their event.

First of all to set the conversation I think I need to define specific and special preparation

“General Physical Preparation, also known as GPP, lays the groundwork for later Specific Physical Preparation, or SPP. In the GPP phase, athletes work on general conditioning to improve strength, speed, endurance, flexibility, structure and skill.[1] GPP is generally performed in the off-season, with a lower level of GPP-maintenance during the season, when SPP is being pursued. GPP helps prevent imbalances and boredom with both specific and non-specific exercises by conditioning the body to work.[2]” Wikipedia 2016

“Specific Physical Preparedness (abbreviated SPP), also referred to by Sports-specific Physical Preparedness is the status of being prepared for the movements in a specific activity (usually a sport).

Specific training includes movements specific to a sport that can only be learned through repetition of those movements. For instance, shooting a free throw, running a marathon, and performing a handstand all require dedicated work on those skills. An SPP phase generally follows a phase of General Physical Preparedness, or GPP, which lays out an athletic base from which to build.”

Related movements that mimic certain aspects of the movement which can be specialized in and put together to form it are also part of specific training.” – Wikipedia 2016

Having a good base of general preparation can have a huge impact on an athlete’s performance in their sport as it allows them to do a whole raft of things that might have been physically impossible prior due to their lacking in basic conditioning. A lot of the changes in modern rugby union for instance have come from a far better understanding and implementation of simple general training principles in strength, power speed, nutrition and conditioning. The change in player is such that teams from as recently in the past as 1995-1996 when the game went professional would probably get swatted aside by a lesser nation in the modern era just down to physical size winning the collision area of the game and matching them in the set piece areas so crucial to generating momentum would probably be nigh on impossible due to their lack of mass and stature.

Anyone strength and conditioning coach who comes from a strength sports background who has tried to work with an athlete who isn’t a lifter will probably have come across some of the following comments

- I’m a “insert sport here” not a weightlifter/strongman/powerlifter

- I don’t squat that deep ever in my sport

- My sport takes place on one leg I think I should be training more on one leg

- I want to train to be “explosive” not lift heavy weights I think I should do more “explosive” work. By explosive they are referring to spazzing about with light weights and learning how to perform tricks utilising a ladder and a bosu ball.

- How is this going to help me to kick/catch/”insert skill here” better.

And you will of course either scoff, shake your head or laugh it off because in your mind they are in the gym to get “strong”, “powerful” or “fast”. At what point does getting stronger in the gym lifts or the big lifts stop helping an athlete to be stronger in contact, what point does power cleaning stop helping them jump higher, run faster or break contact and at what point does squeezing 100th seconds out of their linear 10-20-30-40 meter sprint from an obtuse start make them quicker in open play?

These are not easy questions in field sports because she is a complex and chaotic beast that refuses to share her secrets. In sports like hammer or shot putt it is easily feasible to hone in on the exercises in the gym or on the field that make a difference to performance because we have a beautiful objective standard of performance thrower X throws object Y, Z distance. Now let’s correlate all of these lifter’s performance in the gym and in other tasks against their sporting results and then boom we get instant insight into what is relevant to sports specific performance and what is not.

We can do the same with various stats and game specific instances however we skate on thin ice because decision making, context and skill level are huge factors in a lot of the success/failures in games or field sports such as soccer, rugby or netball. To try and illustrate some of the work that has already been carried out in this vein please take a look at the following abstract:

The relationship between physical fitness and game behaviours in rugby union players

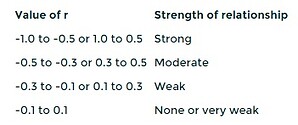

The physical preparation of team sport athletes should reflect the degree to which each component of fitness is relied upon in competition. The aim of the study was therefore to establish the relationship between fitness-test data and game behaviours known or thought to be important for successful play in rugby union matches. Fitness-test measures from 510 players were analysed with game statistics, from 296 games within the 2007 and 2008 calendar years. Sprint times over 10, 20 and 30 m had moderate to small negative correlations (r) with line breaks (0.26), metres advanced (0.22), tacklebreaks (0.16) and tries scored (0.15). The average time of 12 repeated sprints and percentage body fat in the forwards, and repeated sprint fatigue in the backs had moderate to small correlations with a measure of activity rate on and around the ball (0.38, 0.17 and 0.17, respectively). These low correlations are partly due to uniformly high physical fitness as a result of selection pressures at the elite level and leave room for the identification of other key predictors. Nonetheless, physical conditioning programmes should be adapted to reflect the importance of speed, repeated sprint ability and body composition in the performance of key game behaviours during competition. – link to original article

What we have in a study here is a pretty reasonable cohort (510 players which is fucking outstanding for a sports science study!) of a good specific population and we are looking at correlations of 0.15 to 0.38 on game specific performance metrics. Which in the real world adds up to a grand total of fuck all.

This is of course not to say that improving your linear speed times is not sports specific training (however it doesn’t say either that it is sports specific training) the reason for these weak relationships is probably more down to the complex nature of team field sports than it is down to the nonspecific nature of certain physical attributes. What I am using this to illustrate is the enormously difficult nature of trying to develop a sports specific training regime that develops fitness, strength, power and speed qualities that directly impacts on and athlete’s sports performance and aren’t a steaming pile of shite.

Jokers such as the above anonymous assclown who get athletes to do weirdly or pointlessly loaded exercises in obtuse and ridiculous planes of motion aren’t performing sports specific training they are demonstrating how little they actually understand about physics and physical training every time they enter the gym with a client or athlete.

The training principles that underline your more “traditional” strength and power programme that involve high force (squat and deadlift variations), high power (power clean, jump squat or prowler drives) and high velocity (sprinting and jump training) are operating in a solid foundation of training theory and practical results. Where the disconnect between practitioner and athlete can happen however normally happens in two scenarios

- The athlete already performs at an elite level in their sport but isn’t ed coan or Pryos Dimas in the gym so the strength coach decides the athlete isn’t “strong”. This leads to a lot of the strength coach putting their own standards of “performance” right on top of their athlete and them trying to make them a better lifter. This is not sports performance it’s egotistical molding of an athlete in your own mold. Look how much I put on Jimmies squat well done dickhead now he’s to sore to compete well at the weekend and the coach has dropped him.

- You are trying to apply technique standards that are good practice in sports such as powerlifting or weightlifting to an athlete who is adopted in the completely opposite direction and is trying to utalise them to better develop his or her force/velocity profile to make them better at what they do.

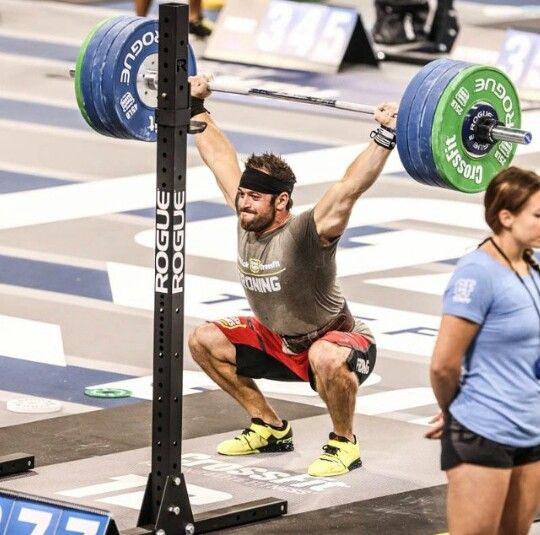

Enter squat depth

By far one of the most contentious issues in modern strength and conditioning how deep should you go in the back squat. In the lifting world there is the black and white of multiply powerlifters and the depth elitism of weightlifters who don’t want to look at anything other than terminal range of the knee and hip joint. There are people in both camps when it comes to the depth an athlete should squat both camps cite their own reasons the pro depth camp believe it displays good movement competency and conveys athletic advantage (with evidence) and the con depth camp believe it carries an unnecessary increased chance of injury in athletic populations (with varying levels of rational and evidence.

What do strength and conditioning governing bodies have to say on the matter?

NSCA Recommended squat depth from their tutorial on squat assessment

The NSCA recommends that depth be determined by the loacation of the hip in relation to the femur. Whilst they (correctly) state that there is no existing evidence that squat depth increases injury risk factors for knee ligaments the reason I am bringing this example up in my article is to juxtapose it with another standard of depth.

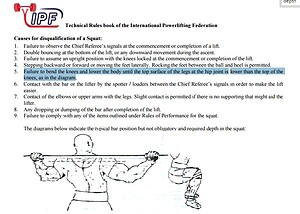

Before there was any need for a governing body to look after the physical preperation of athletes in professional and ameture sport there was a sport named powerlifting. In that sport one of the lifts was the back squat to help referees determine a good lift vs a no lift in terms of how it should be performed a standard of depth was required. The highlighted passage is from the International Powerlifting Federation’s technical rule book.

IPF – Founded 1972

NSCA – Founded – 1978

So when we are squabbling as strength and conditioning coaches about what constitutes a good squat depth it is not uncommon for us to be utalising a depth standard adopted by powerlifting which is a maximal strength sport.

Whilst that might seem like a logical enough anchoring point for some the real question is what does an arbitrary technical rule adopted by a maximal strength sport have to do with the physical preparation of a second row to play a professional collision sport?

Training Specificity is more than just blindly following someone’s lead

The arguments or rants (this I am more than guilty of) that normally follow this discussion are perpetrated mainly by coaches who have too much skin in the game. Coaches who have either decided that to be a great athlete you need to display your capabilities in the weight room or that the weights room is not a good way of training “functional movement” (whatever the hell that term even means).

If you want to understand what training specificity means for your sport then you need to make a genuine understanding to truly understand the game or event inside out, back to front. When you look at “specific” or “special” preparation done well and balls deep into the good you could do a lot worse than to look towards the work of Anatoliy Bondarchuk. Anatoliy is not only an olympic medal winning hammer thrower but he has also coached medal winning throwers in 5 separate olympic games. A lot of the current understanding of special exercises and preparation can be attributed to Anatoliy’s work and book transfer of training in sport.

Anatoliy is the prime example of a coach who understands their sport inside out not only the technical side but also the preparation of athletes and what exercises relate to competition success, which relate to providing a solid physical foundation and how they fit together in the training of a champion athlete.

What we are talking about in most sports is probably a life’s body of work trying to understand the sport inside out and experimenting intelligently whilst constantly reviewing your processes and progress to intelligently review what interventions are providing success. Is the prowler drive a specific preparation exercise for an inside centre in rugby union? Until someone starts to produce training studies and cross sectional surveys that relate back to key performance indicators within that specific role then we have to feign ignorance.

Where should we go from here then?

Where I think a strength and conditioning coach or athlete should take from this article is that the true key to having a really intelligent and successful preparation programme comes from a mixture of factors

- An in depth understanding of all physiological factors that underpin your training practices.

- An in depth knowledge of participation, training and of the sport you wish to prepare your athletes for.

- A scientifically validated understanding of key physical factors that underpin success in your sport and how to train for these traits.

- Use of critical thinking and mini trials to weed out the exercises or training that actually correlates to increases in key performance indicators within your athlete’s or own performances.

What I would like to think that we can agree upon is that athletes are not lifters, they aren’t sprinters, they aren’t throwers, they aren’t jumpers and they aren’t monkeys trained to balance on various implements for other’s amusement.

Training has a massive scope for variety and intelligent application if you want to be an outstanding coach however you need to think before you act and plan thoroughly. Whilst in the knowledge that it is almost a certainty that your plan will require adjustment throughout the entire training process.

Marc